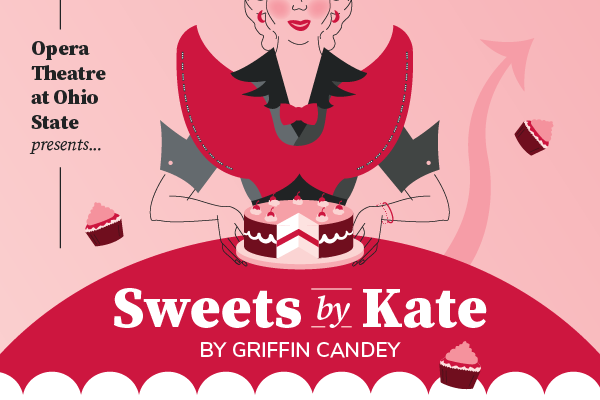

The OSU School of Music is bringing a fascinating-sounding new opera from composer Griffin Candey, Sweets By Kate, under the auspices of director Lara Semetko-Brooks. One of the productions I’m most excited about this season.

I wrote a preview for Columbus Underground and the conversation I was lucky enough to have with Candey, Brooks, and music director/professor Ed Bak yielded what I thought was some interesting discussion on what this kind of new work means to students and the current state of opera. It ran too long for the outlet but I didn’t want it to be lost, so continue reading for those outtakes.

OSU Page: https://music.osu.edu/events/opera-sweets-by-kate-sp22

Columbus Underground preview: https://columbusunderground.com/opera-preview-opera-theatre-at-ohio-state-presents-ohio-premiere-of-sweets-by-kate-rs1/

Correct me if I’m wrong. I think OSU’s school of music generally does about one opera a year; I remember them doing Sweeney Todd a few years ago. Was there any challenge in getting them to sign on to [a project like this], the number of resources, the student involvement?

Ed Bak: Students, no. The students are eager to perform, especially after a year of lockdown with COVID. During the pandemic at OSU, we had no opera at all. It was too dangerous to have people singing on stage near each other. Everybody’s hungry to get on stage and do something. It’s great to give them the chance to perform again. But Lara, you can talk the other, administrative the challenges, the budgetary things.

Lara Brooks: It’s been an incredible coming together with the theater department in collaboration, applying for a variety of grants. To put on an opera, you need lighting designers, costume designers, set designers. We need funding to bring in the composer to work with our students for a week. We need money to bring in Chamber Brews, and we need a ton of help. Dean’s discretionary fund is helping fund Griffin on campus. And then the college of arts and sciences has been so kind and given us another grant to help bring Chamber Brews and to pay for sets, pay for costumes, pay for lighting to make this opera happen.

Because, yes, this opera could be done with just $500. And it is what it is and will let everyone tell the story, but the students are so hungry to have that professional experience. They want to perform with a chamber ensemble. They want to experience, and they want to show the 1950s chipper, happy, almost the Edward Scissorhands town in the beginning. They want that experience and to show the story, to show the juxtaposition of the situation of what’s happening. And we can’t do that without funding.

We have two amazing graduate students who are assisting with the production. Malik [Khalfani] is our conductor, and he’s been fantastic in working with students.

EB: He’s so excited to have this chance, to get involved conducting an opera, period. And then to work with a living composer.

Is it common to have a student conductor?

EB: This is my 20th year [at OSU], so we have had students conduct even in performances. Usually it’s the symphony, the OSU symphony conductor, who will do it. This is not without precedent. But it’s wonderful to include them in, again, a work with a living composer and a score that is not something that everyone knows from a recording, like the Marriage of Figaro.

LB: We have a second graduate student, Bram Wayman, who’s acting as chorus master and coach to the students. And he has been so fantastic working with the students and all the ensembles, making sure everything is clean and clear. The score is so atonal, and so it’s not what the students are used to with Mozart or Brahms. It’s so challenging and he has been fantastic in keeping the students crisp on all the exact notes and rhythms and what’s expected of them.

EB: Exactly. And building confidence. There’s a big learning curve, because it is a musical language that they don’t know. I’m sure the students have not performed other works that you’ve written, [Griffin], and they don’t know what your harmonic vocabulary is like, or they don’t know how these rhythms feel in the body. Not that they’re just counting madly to be accurate, but to feel them. [At this point in rehearsals], we’re past that curve and the scenes are coming to life and the characters are coming out and they’re starting to sense a new kind of beauty.

Griffin Candey: That just warms my heart. I love that. It’s an amazing sort of barrier to cross, you know what I mean?

EB: Absolutely.

GC: There’s so many things in a sort of comedic score like this that are kind of like quick delivery kind of like conversational, but sort of once you do embody it, then it just sort of flows, rather than sort of keeping it right in the lanes, you know?

EB: White knuckled, trying to be right.

GC: For sure.

EB: You came and joined us for our very first sing through, which was really rough, and the learning process was still going on. And a lot of it was unrecognizable and now it’s like, they don’t need training wheels on. I don’t have to double them anywhere. You’ll recognize your piece. I’m so happy that-

GC: I think you’re not giving yourselves enough credit. I definitely recognized it. Any learning process has that sort of… I mean, even things that do have commercial recordings and things, there’s still the early correct versions and then sort of once… whenever you’re sort of in the correct zone, you’re still not fully bringing yourself into the performance. You know what I mean?

EB: Right. And a lot of people don’t get past that with the standard repertoire, because they just imitate a sound that they’ve heard in a recording, and they’re never digging, digging, digging, and having to find the answers for themself. And that is how working on something like this is going to bring their other period, other styles, other composers in a new light to really make it theirs, dig, explore what does the composer mean? Or what does it mean to me?

GC: It’s a lot of gears to turn, to get everyone in the same room for rehearsing and making sure that all the rehearsals are culminating to this thing, with everyone. What I always talk about with any younger composers that are interested in opera, is that if you aren’t cool with people touching your baby, you maybe shouldn’t do it. Inherently in the process, through singers and through coaches and through conductors and through lighting designers and costume designers and directors, everyone is going to get their hand on the ball, and the thing at the end of it is going to be different. You have to want that. It’s not a thing that you should just endure. You know what I mean? If you’re not cool with having that filter through people and trust their artistic vision and their ability and their everything, then yeah, it’s probably not going to be for you.

EB: That’s so great to hear. I’m going to tell you a little story. I got to work with Andre Previn a bit when I was at Tanglewood. We coached Honey and Rue, the song cycle that had just come out. The soprano who was singing it did all of her preparation. She sang and we were talking about the first song. And she said, “Well, Maestro and [writer] Toni Morrison, I noticed you did…” She knew exactly where everything came from. And she said, “The first time it comes, you have the singer at a mezzo piano. But when it comes back later, it’s a piano.” And he said, “Oh, did I do that?” Like he’s not gripping the wheel, not demanding total control.

GC: No. Every time that I come to a first rehearsal, one of the main things that I want to communicate is that I’m not just an omnipresent God that’s waiting to strike you dead. You know what I mean? “You better get this right, or else.” That’s not at all the energy that I’m hoping to bring to a process. I mean, you’ve got to put in the hours, and you got to sort of get it in your body, but I’m also not here to smack your knuckles with a ruler.

Maybe I’m just a happy, doe-eyed, small child, but I don’t know, every time that folks have put their selves and their whole energy into a thing, it’s always made it better. I don’t know. I’ve, luckily, never had someone who’s like, “I’m going to take this whole thing and change all the bones and just completely make it my show and not your show.” You know what I mean? They’re always really trying to bring themselves to it, and in doing that, it’s always been better. You know what I mean? It’s always been a very consummate, satisfying process.

This has, I think, a five-piece version of Chamber Brews. Could you talk about the orchestration?

GC: I knew that I wanted to keep it petite, partially just because I was writing it for a summer festival. If they do full operas, they tend to do it either with piano or with a small arrangement of something, so I knew I wanted to keep it three to five. But very specifically there was a video, that I think has been taken down, of Anne Sofie von Otter singing “Marietta’s Lied” from Die tote Stadt on YouTube that I’ve listened to 800,000 times, that is an arrangement of that aria for piano and string quartet. I mean, string quartet is beloved for many reasons and one of them is just that it’s this incredible arrangement of four people that can be so, so delicate or surprisingly loud for four strings.

And there was something about that arrangement of five. I wouldn’t call myself a pianist, but I write at the piano. Piano and I have a love, hate relationship – we go back and forth. So, there’s something about that five that really has this huge range of delicacy to really sort of heft, that can kind of, I would never say, “Oh, it’s the same as an orchestra.” But if you’re thinking about having a whole palette of dramatic options, you really have a ton of things at your disposal with those four.

EB: Very many times when composers are seeking something new, we’re looking at Schoenberg, we’re looking at late Beethoven, we’re looking at Brahms. [And] the two forms they go to are solo piano works, where there’s one person who can pull all the levers and strings, or a string quartet, which is the mini version of an orchestra that has the possibility of so many colors, so many combinations, but it’s just four people. The ideas, they can reach further and break outside of the box. I think it’s the perfect match for this kind of work, creating something really new.

GC: I’ve talked to folks about making a bigger version and I kind of don’t want to. I mean, full disclosure, if someone paid me American dollars for it, I might maybe do it, but [not] if it was just of my own volition. I know so many folks who enthusiastically dove into opera and wrote the biggest opera possible that requires a way bigger cast than this, with an even wider array of voice types than this does and a pit of 60 plus people, and it’s just never going to get performed.

EB: It’s going to kill your chances of actually getting performances. You might get one.

GC: Yeah. It’s such an odd business. I mean, big companies, especially A-level houses, do so much to preserve their bottom line of being like, “We definitely know that everyone’s going to really, really enjoy us doing Tosca again, even though we did it last year.” Which no hate on Tosca, it’s one of my favorites.

[But] there are also so many of every other size of opera company – especially in the US, but also beyond – that are all doing interesting stuff. There are really big houses, and amazing regional companies, like Opera Columbus is also doing great stuff. Even smaller than that, there are these interesting little mobile companies that are counterintuitively taking way bigger risks. So, I think there is a market out there for small companies that want to do interesting stuff, that want to poke around in new works. The people that I know who either run one of those companies or sing with those companies have a really hard time finding works [that fit their budgets].

EB: And finding an audience. As we all know. In classical music in the United States, there’s a lot of blue-haired people in the audience, and we’re all trying to change that. Not only through the subject matter, but through the presentation. Finding ways to tell the story and to make the format more interactive or more enjoyable, let people know they can laugh at the opera. I think we’re going to see a lot of really, really interesting stuff happen as a result of COVID, for a number of reasons. And this sort of thing, putting the opera on this scale, and conceiving of it this way, with piano and string quartet, that’s the sound of this opera.