The thrust of the story and the definitive version of this is in Columbus Underground here, and I want to thank my editors in CU for commissioning it: https://columbusunderground.com/writers-block-poetry-walks-into-the-sunset-rs1/

I also want to thank everyone – yes, again – for being so generous with their time. I go into a little more detail and let some folks run on at a little more length in this extended cut, and I hope the die-hards enjoy it.

When I heard the Writers’ Block Poetry Night – with a rich history across seven venues going back 24 years – was calling it quits (at least as a weekly event) after the December 21 show, I knew it was something I had to write about.

As someone who grew up in Columbus and turned 18 around the time the night started, I watched the poetry scene blossom into something that would have been unrecognizable just a few years later. And while I wasn’t the most regular attendee, I was always grateful when I made my way through those doors; I always left inspired and usually left with another poet I was checking for. If anyone from out of town was here on a Wednesday looking for something “Columbus,” it was one of my very first suggestions.

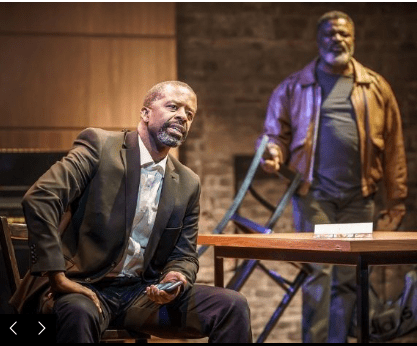

I made it to an event recently, and it’s as irreverent, moving, and powerful as ever – glowing with community and affection for its regulars but encouraging to newcomers. I intended to stay for an hour and get a few photos, but I ended up pushing my other plans back, getting a second drink and staying for the last poet; I was having that good a time. Do not miss these last shows.

I was lucky enough to talk with the three current runners of the event, Kerouac’s owner, and two poets from different periods of the event. I want to thank each of them for being so generous with their time and memories. conversations were edited for clarity and length.

People interviewed:

Vernell Bristow: Poet and Co-Founder, Originating MC.

Scott Woods: Poet and Co-Founder, former President of Poetry Slam Inc.

Louise Robertson: Poet and Coordinator.

Sidney Jones, Jr.: Poet and Teacher.

Zach Hannah: Poet.

Mike Heslop: Owner of Kafe Kerouac

Pre-History

So, how did you originally meet? At [legendary downtown venue] Snaps and Taps?

Bristow: I had been to the poetry forum at Larry’s a couple times. And one day I saw a flyer in the Black Cultural Center, and I said, “Oh, maybe I’ll give it another try. It’s Black people.” I went to [the reading] and met brother Is Said [acclaimed Columbus poet and playwright]. He used to have a series: Poetry in the summer was his thing at Hot Times [Festival]. And poetry in the winter was always on campus in the Frank Hale Black Cultural Center. He introduced me to the series at the Marble Gang [restaurant].

I credit brother Is Said with starting me on my way with poetry in Columbus.

Woods: He was carrying the torch for Black poetry since the late ’60s, at least, early ’70s. And he was doing that pretty much by himself, I guess until Snaps came along. But he always crossed worlds. He was always at Larry’s. Always at Hot Times. He was known throughout the city. He was carrying the torch for us.

Bristow: Before Snaps & Taps, in the same location, was [James Chapmyn’s Living the Dream] theater company, and they had a weekly open mic poetry reading. When it was time for his theater company to go on their college tour, I started hosting it. [Is Said] saw me host. He was like, “Oh, you’re pretty good at that.” So, when Snaps opened and they were having a weekly open mic, they naturally asked Is Said if he would host that open mic. And he said, “Oh no, I’m too old for that commitment. You need somebody young for that. Sister Vernell can do it.”

And one day, this guy, Scott Woods, came walking in with some love poems tucked under his arm and the rest was history.

Early Years

When did the series begin?

Woods: This is always the point of contention. Here… It was ’98. It was the year that the movie Slam came out. Because one of the first gigs that came through Snaps & Taps was getting poached to do a reading at the Drexel Theater for the opening of Slam.

Bristow: When we were at Snaps & Taps, the room was packed every week, but never the same people. Repeat poets would come out. But the audience was never the same people. It was more like people would come out maybe once a month, once every six weeks. Just bunches of people on the same schedule, but on different weeks.

Woods: That’s because it wasn’t a good time. Snaps didn’t serve alcohol. It didn’t serve food. And when it was packed, it wasn’t the most comfortable place to be. And you were subjected to three hours of poetry on a Wednesday night. Those shows were long.

Jones: [Coming to OSU after graduating from LSU,] Snaps & Taps [was] the place to be. It was Love Jones but with way better poetry in a lot of ways.

Bristow: That’s funny.

Woods: Highly debatable, but that was definitely the vibe. And then somewhere along the way, we started caring about what the show was doing.

Jones: Almost anyone I consider a friend today, I met at Snaps & Taps or through Snaps & Taps. I met Scott there, I met Vernell, [I met] a lot of the early poets and a lot of my early associations [moving to town]: Kim Brazwell, Jason Brazwell, Ed Mabrey, people like that.

Slam

For many years, this open mic was heavily associated with Slam in a way I don’t remember having seen in Columbus beforehand. When did that start?

Woods: Not long after we got going. For the record, we were not the very first slam event in the city; OSU used to put on these things they called slams. But technically, we were the first actual poetry reading to put on a slam. We were slamming not too long after we got going; maybe a year. We did our first regional slam in 2000. The first time we sent a team to nationals was in 2001, Seattle.

And I remember I had gotten hip to it online, and I was like, this sounds wild. And at some point, I saw [the documentary] Slam Nation. I kind of got hip to it on the internet, which was tough because back then, all there was, was, like, forums. There was no YouTube, there was no social media. So, I joined an email listserv for slam, and it was dope because back then, like everybody at the national level was tied into the same source. We just kind of did them for kicks.

Bristow: It was just like bragging rights. Like, [Snaps and Taps owner Todd Tuney] he has like 20 bucks [as a prize].

Woods: And they were really rough affairs. Like again, like the poets didn’t really know what it was. We didn’t really know what it was. People were getting really invested in it, which made it appealing to us as a program.

Jones: There used to be a Midwest poetry slam league. Columbus had a team; Dayton had a team. Let’s see. Detroit, Chicago, Kalamazoo, places like that. It was cool.

Woods: Marc Smith, the founder of poetry slam of Chicago had become very uninvested in what was happening at the national level. I met [Marc] in 2000. And he had this idea: “Yo, the Midwest has this really special energy. Slam came out of the Midwest. I want to create a league. It’s basically like a bowling league. I want it to be fun again. I don’t care about all these points and all the stuff they’re doing at the national level. I don’t want to do any of that. But I want to keep it in the Midwest where we have a certain value.” And so, he started the Midwest Poetry Slam League, and basically venues in different cities would have a bowling team of poets.

Jones: This is how crazy we were, right? And this is how crazy I was as an early teacher: the Midwest slams would be during the middle of the week, right? And it would always be some time like… I don’t know. Let’s say 8:00 at night in Detroit. Everyone would get off work, leave school, meet at Snaps & Taps or carpool, drive the three hours or so to Detroit.

Slam would last like… I don’t know. Maybe an hour and a half, two hours. And you’ll slam off against at least Detroit, and maybe another team might be there. And it’s all about like bragging rights. And so, you would have that. And then you would drive back home. So, you get back home at God knows what hour, then I’m up for work the next day. Maybe I got papers graded. Maybe I didn’t. Luckily, I was conscientious about always having lesson plans.

There was a friendly rivalry between Columbus and Dayton. Sometimes Columbus and Cleveland, you had that going back and forth. There was also the Rustbelt Poetry Slam, that was a regional slam, that was an invitational that Columbus has hosted a couple times, Dayton hosted.

Woods: We had rules, but they were very short and not intense. But you had to do group pieces and stuff like that. It was a beautiful thing. Short-lived, because ultimately there was no money to be made in it. And so, it’s very hard to give people gas money. And our team was like 10 folks deep.

Bristow: I think we even had a couple of Dayton people that ended up on our team, Columbus Thunderpants, in the second year [when their team folded].

Robertson: Rustbelt is a single tournament, and the Midwest Poetry Slam League was like, “Go here and then go here.”

Woods: Rustbelt was a two-day competition that would change cities. It was created by [Dayton Poetry Slam founder] Bill Abbott, and then it started bouncing. It was in Dayton for a few years. Then Columbus at least four times [some run by Ed Mabrey]. those were good times, good shows, good showcases of the region: when it comes to performance poetry, the Midwest’s got chops. Especially back then.

Jones: When [school slams were] first announced in the district, my department chair is like, “Hey…” Because they knew I was involved in slam in the past and I had done open mics. Like, “Hey, we’re going to send a team. You want to do this?” And I resisted. I was like, “No. I don’t know if I want to do it.” Because as much as I love poetry itself, I do have a love-hate relationship with slam.

You love the competition, you love poetry events, but the thing about slam is the best poem sometimes, and maybe a lot of times, does not win, right? That’s the nature of the game; there are a lot of other factors that go into what an audience wants. I’m not going to be so bold as to say the audience is wrong. They like what they like. But if you are a listener and a poetry nerd of sorts, you’re like, “There’s no way this poem is as well-crafted as this thing that won.” Sometimes the audience and the judges want more entertainment than they want craft.

And my thought was, “I don’t know if I want to do this to kids.” I don’t know if I want to subject them to this because I know it gives and it takes. And it can lift you up, and you can have some heartbroken times, right? But they talked me into it, and we had a group, And I remember telling them our first meetings, “Look, guys, I’m going to tell you right now: we’re not going to win. We’re not going to win this. So, my job is, at the very least, I want people to know that you can write good poetry. I want you to be good poets. I want you to present good poetry.”

In a lot of ways, I tried to model myself after the way that I was coached by Scott, right? And the things I had learned and seen from my experiences with especially Snaps & Taps, especially the slam team coming out of that venue, just pushing the craft and challenging them. Challenging [the students] like, “Hey, don’t use cliches. Give me something other than an angsty teenage poem about a breakup. And if you give me a breakup poem, make it original. Show me the breakup in a way I’ve never seen it before. This isn’t good enough. Try it again.” I tried to push craft more than anything. And then we worked on delivery. I think we spent probably 80% of our time working on the poems, beating the poems up, 20% of our time working on delivery.

And maybe that’s me, because I never memorized anything, right? But I push that with the kids. I’m like, “If you want to memorize, I will help you with that. You don’t have to [but] if you decide you want to memorize, then I’m going to make sure you do it and I’m going to push you that way.”

And the kids, by and large, they responded. They loved it. They became critical listeners themselves, of poetry. our first team, I think we tied for eighth, out of like 16. I think every school in the district had a slam team that first slam. Then we just kept getting better and better each year; kids got more into it, it got more competitive at the school level to make the team.

National Poetry Slams

Writers’ Block was the first Columbus reading to send representation to the National Poetry Slam (nationals) and sent teams every year from 2001 through 2013.

Jones: I was somehow lucky to be on that first slam team. I don’t know how, because it was a team of heavy hitters. I squeaked by. I don’t know.

Columbus hosted the Women of the World Poetry Slam [another event run by PSI] twice.

Bristow: It was amazing to experience what I had experienced in other cities that had hosted national events. But I got to experience them right here, in my city. Poetry Everywhere. People who weren’t a part of it, but were like, “What is happening?” Seeing the frenzy of everyone wondering what would happen.

Robertson: [At one show, there] was a huge breakdown. [A slam] judge left the room to go to the bathroom, think. And Vernell flawlessly – seamlessly – kept the energy up; kept it even, because if you get too high or get too low, the poets are grumbling they’re not going to get points.

Woods: That [tourism piece] is important, too. The WOW events were not local events; they were not regional events. They were national events. Poets from all over the country, poets who’d been on television, poets who had been in movies, poets who had won prizes, name poets.

Robertson: A few of them international, Canadian, Caribbean.

Woods: [They] came to our city and walked away with this amazing impression of the city. That was like not easy to do, right? Because Columbus is Columbus. But we had to think really hard about putting [this on]. Because we only have a couple of local poets participating in that competition. Everybody else is from somewhere else. We’re talking like 60, 65, 70 poets, All from different places. All the side events, right? We were showcasing our city. Right? We were the reading that did that. We are the people who did that.

Poets, The Audience, and Community

Robertson: [In 2004, when the show was in] Barrister Hall, I had not been writing: job, kids, all that. I had started writing again, and they had a virgin night. I wrote a note to them saying, “I haven’t written in 10 years. Does that mean I’m a virgin?” Then Scott gave the most Scott answer ever. “We’ll see.”

Bristow: That is so Scott.

Robertson: I show up, and I just thought it was great. Then a couple weeks later, I came again and I haven’t looked back. [Staffing came] about a year later; they needed press releases written. Of course, me, kids, jobs, everything, I’m like, “I could write a press release in the middle of the night.” And since I’m a web developer and email developer, I would do web stuff [because] you could do that in the middle of the night too. [When] we had a fundraiser, I set up the digital money [collection] and the microsites with the poets [pictures, bios]. Then I just insinuated myself. Because you really do need three people. You could do [run a show] with two. You can even do it with one; on those very rare weeks where it’s only one, you draft somebody to do the door, greet people when they come in, and you can do it, but it’s like hanging on with your fingernails.

Jones: There’s polite applause. You get that. But you earned the respect for your work too. But you always have to earn your spot too. That’s another thing about Snaps & Taps. even at Writers’ Block, [has] this idea of earning respect through your work. You earn your applause.

Hannah: I came at a time where I probably needed it more than anything else in my life. I needed community because I was a wild one. I had lots of wrangling with language over the years but never had really applied it to any one form or format or medium. Never really put anything into the ether. [About 10 years ago,] I Googled open mics in the city, and Writers’ Block came up. I never had community outside of, like, childhood church. I’d never even been a part of anything [that was] borderline community. Partying doesn’t count.

Robertson: We had a writer by the name of Rick Forman come through and drop these little two-line truth bomb poems that rhyme. Scott, every week would introduce him with a fantastical long, sometimes marathon, 12-minute introduction. And he could always weave into that fantastical castle of words, a lot about poetry. And both Vernell and I had moments when we could introduce Rick, and we had our different shticks and things, but we would also weave structure words. So in an ongoing way, Rick provided a way, not only to be fun and something people expected. It was funny. But we could talk about art overtly and have a great time with this really sweet guy who came every week.

Bristow: When I first got involved, I wanted to celebrate poets. That’s why I loved Scott’s introduction of Rick. We celebrated Rick every single week [and] the essence of poetry. I wanted people to try to find community. Knowing Rick confirmed to me that we did what I wanted to do: create a community. I started running into Rick, outside of Writers’ Block. Rick was like in his seventies, and he had relocated back to Columbus. I would run into Rick’s younger sister. She never came to Writers’ Block, but I would run into her at the Jewish Community Center. One day, she stopped me and thanked me for giving Rick a home when he moved to Columbus.

I think probably my most memorable moment is near the end of Rick’s life. He had been in the hospital I went to go see him. Here he is with cancer, and he is so concerned about how Scott is doing, how Louise is doing, how Marshall [another poet] was doing, how I’m doing. One time, I went to go see him after a long day, and I was so tired. He was like, “Take a nap. I am.” I took a nap in his room. He took a nap in his bed.

But one night, one day when he was in that Wexner [Medical] Center, he was so concerned about poetry that he wrote a poem right there for me to share at open mic. We were his people. I think for me, he symbolizes what I hope Writers’ Block would accomplish, one of the things that it would accomplish, that it would give poets a home and a place to feel comfortable about sharing.

Hannah: Rick had me finish his feature. He brought me onstage to finish his feature for him. I didn’t know it, but it was about Herman the Worm. He didn’t know I had a speech impediment. But I went up there, and Rick probably slapped me in the mouth harder with the last poem he made me read for his feature. I’m reading it for the first time onstage to other people, and one of the last things of his feature is, “You don’t have to hurt for your art.” It was like, I’m reading that, and I’m like, “That’s it.” The crowd was clapping, and I’m like, “Oh, Rick just bodied me.” It was the community that pushed me in the right direction.

Robertson: We talk a lot about fostering good poetry, but we also make sure that [when] somebody comes, they don’t have to worry about the thing they might feel self-conscious about. That’s not the business here. Sometimes readings give a certain vibe, or a certain kind of person does a reading. [Here,] you see a lot of different ages, different groups, different backgrounds.

Hannah: One of my good friends, one of the guys I started poetry with here, Dug of Happy Tooth & Dug, I watched him. It was when we were new. This might have been his fifth or sixth time onstage. He said a word that no longer is used as much – an ableist word – in a poem, and Izetta [Thomas] yelled out from the back and said, “You can do better.” And Dug is like, “What?” She explained to him why and how he can do better. Dug learned from that and Dug came back. Now, Dug is one of the more forward-thinking people I know.

Hannah: I didn’t mention Izetta [yet]. That’s a shame. Jesus Christ, Izetta is one of the best,

Robertson: It’s a community; you end up caring about everybody, no matter who they are. We’ve lost a couple other poets, and it’s just heartbreaking.

Bristow: Gina Blaurock. Oh God. [Gina Blaurock passed in 2015] Bill Hurley.

Hannah: Bill Hurley’s reading of “The Raven” every year, it wasn’t “The Raven,” but it was The Raven.

Hannah: Gina Blaurock was one of the reasons why I felt like I started to gain community here. [She and] Vernell Bristow would go out to pizza with me after Writers’ Block for some five, six, seven months. I don’t know if I would have ventured outside of the stage here if it were not for those two. I had many features change my life on that stage, but the community I definitely got, through the crew: Scott and Vernell and Louise and at that point Gina, were just inseparable, [and] Ed Plunkett [Columbus poet who wrote a beautiful tribute to Blaurock here.]

Woods: [A] definite one is when Marc Smith, founder of Slam, came to our show.[Him] being at the show, seeing the open mic, we did a slam that night. He got up, did his poem. But he said to me that he loved our show because it had the energy and the vibe of what he originally created. “This is what slam used to be like; this is what the old-school stuff felt like.” He was just very proud of the show. I was like, “We’re doing it. This is it. This is the mountaintop. That’s it.”

Hannah: I know it had been going on for a few years beforehand, the murderer’s row of hecklers that used to be at the back. If it doesn’t get mentioned in the story as a part of the culture here, something’s wrong. You could hear the criticism of some of the less careful with their language onstage. You could be listening to both. You could hear the poets say some pretty unacceptable things and hear them in the back going, “What the fuck?” There was always that mid-level to where you could hear it.

That was one of the wilder things about this place as opposed to other shows and other mediums, and other art forms that I’ve seen over the years. Because at a comedy show, a heckler gets singled out. At a music show, if you interrupt the music, if you stop the music, you are enemy number one. Burlesque, drag, so on and so forth. But to have the poets be like, “Fuck him,” from the back as a guy’s reading a poem, that was where it was at. The judgment happened live.

Scott said this is not a safe space to make speeches over the years. I mean, because so many young, heart in a good place, generally white kids would really think like, “Hey …” They all have this knee-jerk reaction that you should not be allowed to say certain things on the stage. Scott proved them all wrong and why over the years because if you had something messed up that the court of general opinion did not agree with, you would find out.

You know, poets aren’t quiet types. People sometimes pay money to hear us speak, you know what I mean? that definitely happened years ahead of the conversation [about] safe spaces. Way before Roxane Gay [and] articles are being shared on the internet, Scott is saying, “This is not a safe space.” I’ve run events over the years and if there’s any influence that Scott had on me was the idea that this is not a safe space, “Say whatever you want, but we’re going to hold you accountable.”

Hearing young cis men poets use the word rape pretty [flagrantly] but to hear afterward over the years in different contexts and settings, different faces or whatnot, to hear them being told afterwards, “Okay, the poem is cool, but that actually hurt me.” To hear how they took it because some have learned. Some have moved forward, and some of them have realized the power they wield with their language. Then others just, again, wouldn’t last because they weren’t welcome here. Sign up. Go up onstage. We’re just not going to listen.

[Once] a kid asked Scott, after Scott had given people some just history of things or whatnot because somebody had asked. A kid said, “If you’re so famous, why are you still a librarian?”

Scott laid into the kid verbally and then laid out a challenge. He said, “You want to write some poems and have a little showdown?” The kid very, very reticently – he was not excited about it – said, “Okay.” Honestly, my memory doesn’t serve me if it was that night or the next week. But they went outside, and I’ve been in a lot of poetry ciphers and people reading around. A lot of sex noises coming out of people listening. I have never heard like, “Ooh. Damn,” so much as when Scott obliterated that kid.

He murdered him. It was violent. The very last line of that poem says that the kid is dead from the neck up. People lost their shit. They were spilling out into the road. So poetry got taken to the streets like rap battle style, sans mic.

Woods: We gave Hanif [Abdurraqib] his first feature.

Robertson: Gave a lot of people their first feature.

Woods: Yeah. But you know, only one that has a [MacArthur] genius grant.

Woods: One of the purposes of the Writers’ Block Poetry Night, very specifically, is that I’ve always wanted to be a place where people could go in Columbus, and you don’t know what’s going to happen. I wanted it to be a place where you can still be surprised by art.

Venues

Between the early gestation period at Snaps and Taps and the stability of Kafe Kerouac, Writers’ Block went through five other venues, to mixed reception, growing pains, and sometimes scant audiences.

Woods: [We went through downtown coffeehouse] Skambo, Casablanca, which was an African owned bar…

Bristow: Down by the Courthouse. We showed up one day with their bartender, and we found out together that it had permanently closed the week before.

Woods: That was extremely short-lived. After that, we were in Barrister Hall [storied Columbus jazz and cigar bar, now closed] for a while [where Louise joined]. And then [we moved to] Columbus Music Hall [which was] like, “Y’all got to…” The show was almost dead at that point in the water.

Bristow: They had scheduled something else. We were on their website noticing that they had something else scheduled for our time [without telling us].

Woods:. In all fairness, nobody was coming to the show at that point.

Bristow: we had like eight people, 10 people [in a 100-capacity room].

Woods: I immediately hit up Mike at Kerouac because he’d been hitting me up at that point for at least a couple years. Kafe Kerouac is like the fourth Beatle here, right? There’s something to that space that lets you get away.

Heslop: I saw Writers’ Block back when they were in Barrister Hall. When I started Cafe Kerouac in 2004, I always wanted to get Writers’ Block involved in having a show there. It took a couple of years to lure them over. I think Writers’ Block poetry was a big part of helping us create our identity and expand our customer base to a lot more people around the city because they were able to draw in poets that may not have heard of us otherwise.

Woods: I’ve always loved trying to figure out what we can’t do in Kafe Kerouac. I haven’t come across anything. Kafe Kerouac is very punk to me. Right? It’s very “old campus.” Once those doors close, we make no promises. We won’t physically hurt you. That’s all.

Robertson: It makes you feel like you don’t have to be worried about breaking something. You can do your thing, and you can throw the paint, and you will not be a bull in a China shop. You will not be hurting anything. We really have to give a round of applause, and we do every week, for Mike Heslop. [He] is the most gracious [partner]. I’ve been around since Barrister Hall, and the relationship with the venue owner is sometimes rocky, sometimes filled with restrictions, because they’ve got a business to run. But Mike has been, do what you want. You are good for business. We have just found some degree of home.

Heslop: I opened Kerouac to have that old vibe where it was disappearing. There used to be other venues like Larry’s Bar that used to host poetry and things like that. I grew up at OSU campus, I went to Ohio State, and all those independent little quirky spaces have disappeared over time and been replaced by Targets and Starbucks and those type of things. I see Kerouac as “Let’s push the limits a little bit; let’s have fun with it,” in the sense of art and simplicity of it, but I don’t take it too seriously. It’s supposed to be a casual artist hangout, and I think Writer’s Block did and does a great job in making everyone feel welcome.

Woods: For a long time, as an MC, I was always trying to make this show more entertaining and engaging. I was always adding these games and little tricks to the show. And then eventually, it was just like, why does this feel like work? I was doing those things since I thought it would add audience. And the audience would fluctuate wildly.

Ultimately, I just had to sit down and break everything down to its last compound and say, why do people go to poetry shows. Why that’s presumably to see poetry. Instead of trying to create this experience, I was like, “Yo, we got to strip this thing back down to the poetry, and then we can sprinkle some stuff on top.” And that would be the show.

That’s essentially what we have now. We make it look easy, but that took years to learn. And a lot of people come to our show, and they see us engaging with the audience and the banter. But they think that we are like doing a process, right? it’s not. We’re just greasing the wheels for the people who are actually here.

Robertson: The modifications we make intentionally all foster better poetry in very subtle ways. We’ve gotten down to a system, and the introduction of the [one poem] rule was one. I don’t know if the rule came – it didn’t come first. But we made people only read one poem [instead of the standard poetry reading two-poems-or-five-minutes]. Two magical things are: if you have to pick one, you go for the good one. Like, not to say that there’s not good ones.

Bristow: And that one poem [rule], it kept that show moving really fast: get them up, get them down. You can get more poets, you know? Because when we were doing two poems, it would be a three-hour show, and sometimes we would have to tell poets, “Come next week, we’ll put you up early.” It would just be exhausting. I think one of the things [that led to that] was when we created a monthly show called First Draft [you could only bring new poems to].

Robertson: It changed the culture of the show. See that guy with that poem you heard 22 times, and you’re like, “It was a good poem the first time.” But it fostered the culture of writing. And now, sometimes I feel like we’ve gone too far. Because people are afraid to repeat, and you’re like, “No, no, no: good poem. I want to hear it again.”

Woods: Which is why we killed First Draft.

Woods: We seem unassuming. If you’ve been around the block a little bit, when you walk in there, you don’t get the vibe like, “Oh, this is like the nationally lauded Writers’ Block Poetry Night. You’re just like, “This looks like just a regular poetry reading situation.” People who don’t really know what we’re about, they learn really quick that there’s something under the surface happening there. We’ll go pound for pound on the poems, on the awards, on whatever you want, publications? Like, how many books you got? Blam! Blam! We will run it all night.

Bristow: All night, all night. Every now and then, someone like that will come in, and they have no idea who we are. They will come in wanting to educate us about poetry slam. One of the most ridiculous moments is this young person gets on the mic and says, “I’m going to read a poem by another poet. You guys have probably never heard of him. His name is Buddy Wakefield.” It was just all out laughing. He’s like, “What? What?”

Woods: It’s like, you mean the Buddy Wakefield who slept on my couch? Is that the one you’re talking about?

Hannah: I tattooed myself [on that stage] during MeatGrinder. I’ve been in a gimp suit during a poem, being beaten and shocked and flogged. I wielded a chainsaw to my baby nephew.

Legacy in Columbus and the Poetry Scene

Bristow: Because people met at our nights, got married after meeting at our nights, spawned children after meeting at our night, sometimes got divorced after coming to our night.

Woods: So many things, probably an incalculable number of things, have sprung out of a little silly Wednesday night show, right? Holler, because of what we do on Wednesday nights. Writers’ Block made all of that possible. The things that we brought, the things that we made possible in this city… You probably won’t even get those stories until we’re done. People will feel the impact of not being there, and they’ll recall it.

Woods: Half of the readings that have ever existed in the last 20 years are because of that show. Certainly, I would say 90% of good poets in this town have had to come to [our] show. I think most poets set out to change the world. The Writers’ Block Poetry Night didn’t set out to change the world, but it did change the city.

Robertson: One of our regulars, Su Flatt, had a project with Columbus State. She was creating an online resource of people reading Shakespearean, all the sonnets. She recruited from Writers’ Block and elsewhere and people were assigned or chose sonnets. Right in this room, they did a big day of recording. You had Scott, you had me, Vernell like all these different styles of writers and readers. That came out of Writers’ Block. She had that go-to resource of dozens of poets who could just come in and give their all to it. It was great.

Woods: It’s important to note that Streetlight Guild wouldn’t exist without the Writers’ Block Poetry Night. It’s a direct line because Glen Kizer, the guy who made this investment possible, was a regular attendee at the Wednesday night shows. He’s not there trying to be a better poet or anything. He just wants to connect with people. Be a part of a community. Every once in a while, he might read a little poem or something, but mostly he would just watch the shows. It was a place for him to kind of connect with people and laugh and be himself. He would get up and read these poems that were very personal, and he would occasionally cry. There was a place where you could do that.

Jones: There is no way I would have been a slam coach [in the Columbus City Schools] without first doing it through my experiences with Snaps & Taps and Scott. I think a lot of that is a stepchild of Snaps & Taps and Writers’ Block. And he would never admit this, but [the students] are like the Grandchildren of Scott Woods to a degree, just in the way they’ve been coached. A lot of them have found their way to Writers’ Block, right? They’re like, “Hey, I’m going to Writers’ Block. And Scott said hi,” or whatever, because Scott would ask them where they went to school. They would mention me. Then he would give him hell.

Robertson: Columbus got a reputation for being a fantastic place not only to put on an event, but how many times people have used the cliché: is there something in the water? Because of the number of just phenomenal writers that are here. Writers’ Block is a big part of the ecosystem that welcomes poets, meets them where they are, doesn’t force them anywhere, and yet somehow lets them flourish.

Hannah: Writers’ Block is my glue. This was the lab. This is where I tested all the crap that I do. I’m on a circuit of punk houses and such in the Midwest. I’ve built a pretty sincere network across these punk houses in the Midwest or whatnot of people who know that I will actually listen and engage with them if they need it. When I do these punk shows, I will start off being loud and catch their attention. Then make them feel things, which they’re not accustomed to. Bucking expectations is definitely something I learned there on [the Writers’ Block] stage.

Saying Goodbye and What’s Next

Woods: It was my idea. I had flirted with the idea of ending it in the past, but it was only an idea. And usually, I was coming from a place where I was really burned out. Usually, Louise would talk me off that ledge. But this time around, it just felt right. Columbus has changed a lot over the years and especially the arts scene. Once we got settled in Kerouac, you could pull a pin on a grenade in that room, and we would still do the show. You know what I’m saying? The audience would still show up, poets would still show up, and one of us would MC. Even when there was no power in Kerouac, we did the show. That show was basically indestructible in that way.

Jones: I don’t begrudge him for this, but it is going to leave a vacuum. It’s definitely going to be missed. And it’s something that I would like to think that someone or someones would follow this example, at least pick up the baton, and go forth like, “Hey, let’s build on this legacy.” [So it doesn’t] just live on in people’s memories but lives on in someone taking this blueprint of what a good poetry night could be and maybe going in a different direction but still having some of those same elements. That’s my hope. And there are a lot of young and new poets who are doing similar types of things as Writer’s Block.

Woods: I’ve spent a lot of years doing stuff for everybody else. And I’m just in this season of my life where I really want to do certain things as an artist, as someone who creates things for myself. I have a lot of titles, but I am a writer. As a writer, it doesn’t take much to knock you out of your lane. An email knocks you out of the zone, a phone call knocks you out of the zone, social media knocks you out of the zone, taking the trash out knocks you out of your zone.

I needed to get out of several commitments so I could get down to what I’m doing. Because I’ve got four books sitting on the table looking at me like, “When are you going to finish us?” I’m like, “Well, I think I’m going to finish one of you this year. Or maybe next year.” We’ll see what happens.

Hannah: The way Scott runs this show would prime the audience to be accepting of many different ranges of entertainment. At other open mics where the poetry largely runs the show itself, and a host just brings people up, the audience, I could see getting tired or having low expectations; they don’t pay attention. I think Scott and Louise and Vernell were the magic. They kept this space what it was, the irreverent open mic because of the essence of all the irreverent poets that kind of gathered here over the years didn’t hurt. But that irreverence is why the stage kept being fun.

Bristow: In previous times when Scott would bring it up, I would be like, “Yeah, I don’t want to hear that. No.” And then it was brought up at the beginning of the pandemic when we couldn’t gather and all that stuff. And I was emphatically: no.

For all the reasons that we talked about. While Writers’ Block was wonderful, I did not want it to go out like that. I did not want it to be a casualty to COVID like so many other things in the city. Louise was like, “Let’s do Zoom.” And I was like, “yeah, girl,” because I thought at that time, we owed it to this thing that we created

Then we came back this April of 2022, and it was great. Every show has been great. And a couple weeks ago after a great show, the next day Scott [brings it up]. And I was like, “wow, we had such a great time last night.” But I thought about it for a second. And I thought about for me personally, what that would mean.

My life has changed a lot in the past couple of years. I’m working full-time. I’m also earning a doctorate degree, and I don’t know what wonderful things will await me when I claim that degree in a couple years. For the first time when he said that, I wasn’t like, “No.” I was like, “Why do you want to end it?” And we had a conversation, the three of us. At least for me, every goal that we had for Writer’s Block, we had already achieved it. . I liked the idea of going out on top. I wouldn’t want to see it die on the vine. I wouldn’t want to see it trickle off with five, six people in the audience. Nothing lasts forever, let’s move on to the next thing while we’re still young enough to make it happen.

Woods: Wednesday night is awesome. It’s obviously working, but I’m like, “what are we waiting for? We’re not going to hand the show off [to someone else]. What are we waiting for? Are we waiting for one of us to die? We’re all 50 or older. I’ve been doing this show for half of my life. Louise was almost a completely different person when she started into the show. Let’s go out on top. Whatever it is that we have to offer, we have nothing left to prove.

And I will tell you that I still like doing poetry shows. If one of us gets an itch to do it, then we’ll go posse up, and we’ll do it. Every once in a while, Writers’ Block will poke its head up, we’ll do something that nobody else can do. We’ll do some wild, crazy show and then we’ll go home. We won’t have to move the chairs. We’ll just leave.

Let Columbus figure it out. It’s okay. We’ve been doing it for longer than a generation. I think it’s okay for another generation to figure it out.

For more information about Writers’ Block poetry, visit their Facebook.